Haemophilia

Haemophilia is a blood condition that means bleeding does not stop[1]. It is a rare condition that affects the blood's ability to clot. It's usually inherited. Most people who have it are male.[1] A person with haemophilia is called a haemophiliac.

People with hemophilia lack proteins in the blood that make scabs and blood clots.[1][2] For example, a child with haemophilia A does not enough clotting factor VIII (8) in their blood. A child with haemophilia B does not have enough clotting factor IX (9) in their blood.[1] People with hemophilia do not bleed more than a normal person, but they bleed for much longer.

In some cases, a boy is born with haemophilia even though there's no family history of the condition. In such cases, it's thought the gene change developed spontaneously in the boy's mother, grandmother or great-grandmother, but until then, a male member of the family had never inherited it.[1]

Some studies have shown there's no known family history of haemophilia in up to 1 in 3 new cases.[1]

The word comes from the Greek words haima ("blood") and philia ("to love").[3]

Symptoms[change | change source]

The main symptom is bleeding that does not stop. People with haemophilia may have:[1]

- nosebleeds that take a long time to stop

- bleeding from wounds that lasts a long time

- bleeding gums

- skin that bruises easily

- pain and stiffness around joints, such as elbows, because of bleeding inside the body (internal bleeding)

There's a small risk that people with haemophilia may have a bleed inside their skull (a brain or subarachnoid haemorrhage).[1] Symptoms of a brain haemorrhage include:[1]

- a severe headache

- a stiff neck

- being sick (vomiting)

- a change in mental state, such as confusion

- difficulty speaking, such as slurred speech

- changes in vision, such as double vision

- loss of co-ordination and balance

- paralysis of some or all the facial muscles

Call an ambulance.

Problems (anatomy)[change | change source]

Symptoms include easy bruising, and hematoma formation. Bleeding from the gums and mucous membranes is another.[4]

The concern is when there is bleeding into joints, particularly in the ankles, knees, and elbows, which is called hemarthrosis. Hemarthrosis can cause an inflammatory process to begin in which the joints become painfully swollen and eventually limit motion. Bleeding into muscle tissue from minor traumas can result in anemia and compression of vital structures and nerves leading to compartment syndrome. Bleeding less frequently occurs in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts. These patients are at significant risk of intracranial bleeds which would be a life-threatening emergency.[4] This can lead to a perpetual cycle of other problems, which then cause the same problems or existing ones to become worse.

If a joint bleed is not treated, it can lead to:[1]

- more severe joint pain

- stiffness

- the site of the bleed becoming hot, swollen, and tender

Types[change | change source]

There are 3 types of haemophilia:

- Haemophilia A - about 90% of cases. There is no blood clotting ability.

- Haemophilia B - not as severe, but much less common. There is not enough blood clotting ability.

- Haemophilia C - caused by not one, but two recessive (weak) genes.

Genetics and frequency[change | change source]

When there is family history of haemophilia in someone trying for a pregnancy, genetic and genomic testing can help find out the risk of passing the condition on to a child.[1] This may involve testing a sample of tissue or blood to look for signs of the genetic change that causes haemophilia. Blood tests can diagnose haemophilia and find out how severe it is.

Hemophilia can present in infancy with cephalohematoma formation after vaginal birth and with more than usual bleeding after circumcisions.[4] If haemophilia is suspected after the child is born, a blood test can usually confirm the diagnosis. Blood from the umbilical cord can be tested at birth.[1]

Haemophilia A happens in about 1 in 5,000–10,000 male births.[5] Haemophilia B happens in about 1 in every 20,000–34,000 male births. If there's no family history of haemophilia, it's usually diagnosed when a child begins to walk or crawl.[1] Mild haemophilia may only be discovered later, usually after an injury or a dental or surgical procedure.[1] The bleeding may also happen after a medical or dental procedures such as having a tooth removed.[1]

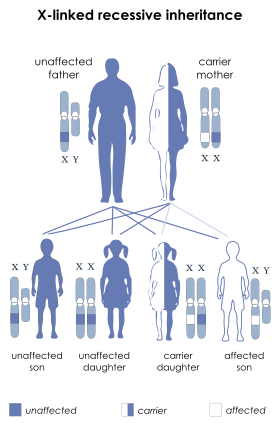

Genetic defects on the X chromosome affect males because they have only one X chromosome. In females, a recessive gene is usually masked by a normal gene on the other X chromosome. The gene change is on the X chromosome. It can be carried by either the mother or father, or both.[1] But The chances of a child inheriting the haemophilia changed gene depends on which of their parents has the changed gene.

The Y chromosome does carry some genes, but far fewer than the X chromosome. Defects of this type are called "sex-linked" in genetics. There is no cure for this disease but there are different treatments available around the world.

Treatment[change | change source]

There's no cure for haemophilia, but treatment usually allows a person with the condition to enjoy a good quality of life.[1] Man-made clotting factors are given as medicines to prevent and treat prolonged bleeding. These medicines are given as an injection.[1] Injections are given differently in mild and severe cases according to the patients needs.

To treat this, an affected person can get a blood donation from someone without hemophilia. The donor’s blood has clotting proteins and can temporarily make a normal scab.[6] 30% of hemophilia A and B cases are the first person in their family to have hemophilia which is the result of an unexpected mutation (this means that there is an unexpected change in the body).[2]

If you received a blood transfusion or blood products before 1996, there's a chance you may have been given infected blood (HIV, Hepatitis).[1]

References[change | change source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 "Haemophilia". nhs.uk. 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2024-05-31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Green, David. "Hemophilia." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2016. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ Douglas Harper. "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Doherty, Tara M.; Kelley, Ashley (2024), "Bleeding Disorders", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31082094, retrieved 2024-05-31

- ↑ "Hemophilia B". Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ↑ "HEMOPHILIA." SICK! Diseases and Disorders, Injuries and Infections. Online Edition. Detroit: UXL, 2008.